![]()

Left: Bee Shaffer and Anna Wintour at the Chaos to Couture opening. Right: Springtime for Sid in Paris.

"Pink is punk." Thus spoke Anna Wintour at the benefit gala that marked the opening of the exhibition, Punk: Chaos to Couture, held on May 6 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Wintour, the British-born editor-in-chief of American Vogue and artistic director for Condé Nast, is a member of the board of the Met's Costume Institute (for which she is reported to have raised more than $100 million), and an Officer of the Order of the British Empire. Apparently even the queen of England can appreciate the regal power of ad revenue and corporate expansion spiraling ever heavenward. "This blessed plot, this earth, this realm …" And yet the pronouncement, "Pink is punk," which slipped so assuredly from Wintour's perfectly thin lips, is both vexing and revelatory. While Wintour is not to anyone's knowledge developmentally disabled, her remark is quite possibly the single most retarded thing any public figure has said in recent memory. Even as retardataire as the fashion industry may be, endlessly passing off the old as new, feeding on its history and ours, since vernacular style—how we dress ourselves in the every day—fuels the more vampiric elements of this industry, the remark is cause for concern. She made it, of course, to defend the dress she wore to the gala: Chanel haute couture, floor-length, flowery pink. It would not have been out of place had she strolled onto a manicured lawn for a tea party at Sandringham.

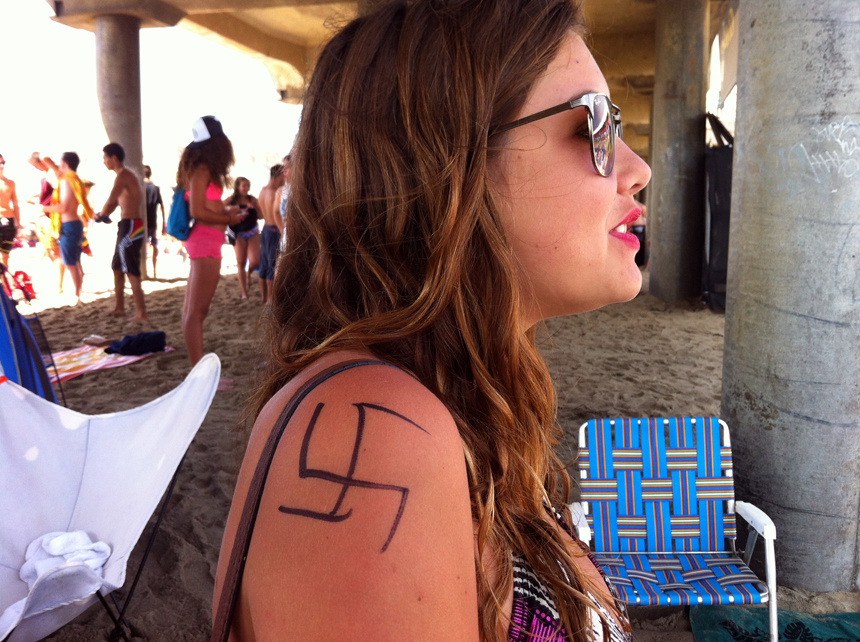

The dress, however tasteful, was worn to a rather different event, the opening of an exhibition that meant to show the influence of punk on fashion. Maybe Anna Wintour was playing against type? A more caustic observer might remind you of Coco Chanel's less than glamorous exploits as a scheming businesswoman in wartime France and her opportune connections to high-ranking Nazi officers, as well as of an infamous image of Sid Vicious in 1976, strolling casually down a Parisian street, wearing a black leather jacket and a T-shirt emblazoned with a swastika. Now there's an intersection of fashion and antisocial realism. "Vicious," as Lou Reed once sang, "I'll hit you with a flower." Punk's flirtation with fascism may have little to do with that of the legendary designer, and yet fashion's very autocracy—to borrow an admission from the show's curator—and its obsession with surface effect, compels us, particularly as we stand beside this newly opened grave, to dig deeper. The fact that Chanel has been dead for more than 40 years has not in any way interrupted the brand and its profits, pointing uneasily to the necrophilia of fashion, to the disposability of its innovators and icons (Coco today would be quite the liability), to the very pragmatism of the industry. Pragmatically speaking, art and ideas are merely a means to an end, and best left to others. If this sounds even remotely similar to the modus operandi of the music industry, it should come as no surprise. Posthumous recordings of Sid Vicious and the Sex Pistols far outnumber those released in their attenuated lifetimes, their earning power exponentially increased in the wake of their demise. Perhaps Anna Wintour's Chanel dress suggests a reversal that accounts for the monetization of the death drive: it's all black on the inside and pink on the outside. As goes the perennial swindle, maybe pink is the new black?

God Save McQueen

"Pink is punk" reveals that the New York fashion industry and its sometime institutional handmaiden, the Costume Institute at the Met, its curators and the tacit captain of both ships, Anna Wintour, wouldn't know what punk is or was if it bit them on the ass. It was bound to be this way. Too bad it wasn't bound and gagged. As with most mausoleums, there isn't a pair of bondage trousers large enough to contain the Met. (They might have commissioned John Galliano for a spectacular wrap à la Christo had the timing been a tad less… unfortunate. Quite the reminder of Jack Smith's proclamation: "Fashion is an ugly business.")

![]()

Left: BCBG. Right: CBGB.

Chaos to Couture arrived on the heels of the Met's blockbuster Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, a critical and box-office success, with its glowing reviews, lines up the block, and extended hours to accommodate the crowds. Both exhibitions were organized by the British-born Andrew Bolton, curator at the Costume Institute, formerly at London's Victoria & Albert Museum, and one show no doubt led to the other. In their intermingled titles we are able to grasp how the taming of an unruly force and the refinement of primal energy is the realm not only of fashion, of museums, and the corporate world, but of all the institutions of social control. In short, everything that subculture stands in opposition to. That is, until it has been expropriated, watered down, and picked clean from the bone. Culture vultures forever circling in an ominous sky. On a recent overcast Saturday afternoon, the only lines in front of the Met were for the hot-dog carts parked at the edge of Fifth Avenue, the sidewalk clogged with tourists and vendors. One young girl wearing a Kurt Cobain/Nirvana T-shirt maneuvered the gauntlet to wend her way up the museum steps, recalling fashion's last plunder of rocky youth culture, grunge, and the brief ascendance of what was designated as "heroin chic." Kate Moss on the cover of Vogue UK in 1993 seems oh so long ago. Nearly as distant as Cobain's raspy voice on "Milk It," where he admits, "I am my own parasite / I don't need a host to live." The line is punk through and through, infected by the kind of nihilism that can either be liberating or self-destructive, and for some it's one and the same. While there are any number of ghosts haunting Chaos to Couture, fashion can't help but distill effects to their essence, and the darkness that often fuels art is reduced to nothing more than a perfumed nightmare. Even the word destroy has been laid to waste, while life and commerce go on. As with the house of Chanel, that of McQueen prevails long after the designer took his own life. For anyone who even half expected Chaos to Couture to create one-tenth the stir roused by Savage Beauty and the staggering achievement of McQueen, they would be sorely disappointed.

A Cheap Holiday In Other People's History

New York may be the city where punk was born, but plenty of veterans of its mid-to-late 70s heyday, and a few fellow travelers, couldn't even be bothered to take the subway uptown for the inevitable letdown. One friend offered the following assessment from afar, and a hilarious take on the "mohawk" sported by Sarah Jessica Parker at the gala [sic]:

"I passed on the Met salute to punk… I find the mannequins there hard to get past in the first place... were those dummies all hoarded from a Halston bankruptcy clearance sale? Debbie Harry was quoted saying there was way too few Sprouse, so natch that dampened my enthusiasm... as did the knowledge that they never consulted with McClaren's estate. Hopefully Iggy gets some due... tho I fear the Met's view might hover closer to a Gwen Stefani view of punk. The opening (usually the must-see of must-go's) looked dreary considering the possibilities with that theme... SJP's 'strap-on' looked way more Super Chicken than Annabella. It seems a sad state of our pop culture when it's Myley Cyrus that had the lone good look of the night... props to her." 1

Another wrote:

"A chimera of a movement within a fleeting moment if ever there was. I know so many people whose versions of that period and what it meant/means are utterly at odds with one another, including my own. To me SoCal hardcore bands in 1982 feel even less punk than Sarah Jessica Parker in a fauxhawk on the red carpet in 2013." 2

![]()

Left: Throbbing Gristle in custom camo gear, 1980. Right: Mark E. Smith fronts the Fall, 1977.

This remark raises a significant point: the contentiousness of a supposedly shared history. It's important to grasp how many facets punk had before, during, and after the fact, how far it spread, its delayed reaction and side effects, and how long its afterlife has been. (This last point remains bewildering to many who were there in that blink of an eye, and moved on.) Rather than for its substance, its roots and complexities, for its fucked-up, entangled history and its many contradictions—political/apolitical, inclusive/cliquish, antiauthoritarian/policed from within—the fashion industry sees punk as style—and not only. Haute couture by way of punk undeniably proves that you can make a silk purse from just about anything. At its most opportunistic, fashion reduces punk to a one-dimensional ready-made with which it can avail itself for its own impeccably frayed ends. While those on stage inevitably give an image to the music, either consciously or not, one of punk's central through-lines is the effacement of the space between audience and performer—all but anathema to high fashion.

In the Met's exhibition, what you'll see are only the faintest traces of the many lines that lead into and out of punk, crisscrossing over time and doubling back on themselves. There is protopunk, best exemplified by the Seeds, the Sonics, and the Monks, followed by Iggy and the Stooges, the Velvet Underground, and the MC5. (Black as the new black, leather jackets, tight pants, and sunglasses after dark.) There's the prepunk glam of Alice Cooper, T-Rex, Bowie, Roxy Music, and the New York Dolls. (Possibly the most fashion-conscious scene of all, and ripe for the picking.) The postpunk of Joy Division, Wire, the Birthday Party and the Fall, as well as the industrial soundscapes of Throbbing Gristle, emerged from the early years of punk, yet in their sound and appearance they set themselves apart. (Here the various looks ranged from gray, pleated trousers and white dress shirts to rumpled overcoats and dorky sweaters, from biker boots and cowboy hats to aviator glasses and camouflage gear.)

![]()

Left: the Slits. Right: Lora Logic and Poly Styrene with X-Ray Spex.

The mid-to-late 70s also saw punk overlap with black culture, particularly in England, where reggae, ska, dancehall, and social interaction with the West Indian community were influential. Records by Alternative TV, the Pop Group, and the Slits were produced by Dennis Bovell, and one of the best early recordings from the Clash was a cover of Jamaican singer Junior Murvin's "Police and Thieves," while Public Image LTD, led by ex-Pistol John Lydon, was heavily influenced by the deep bass and elasticity of dub. Poly Styrene, the vocalist and lyricist for the band X-Ray Spex, was the most visible mixed-race performer on the London punk scene, with parents who were British and Somali. But while the casual geekiness of her look—dental braces, surplus military helmet, and a leather Hefty trash-bag dress—fit the image of songs like, "Oh Bondage, Up Yours," she would not have made it across the red carpet to the Costume Institute at the Met.

![]()

Left: Poison Ivy and Lux Interior of the Cramps. Right: the Ramones at CBGB, 1976. Photo by Roberta Bayley

Stateside, two bands who arrived at their look and sound, one uncannily embodied in the other, deserve particular mention. The Cramps, who came to New York by way of Cleveland, though spiritually they hailed from a backwoods, Southern swamp, were purveyors of a psycho-rockabilly and always dressed the part. When they performed their now-legendary show at a mental hospital in 1978, the "third wall" of the stage was instantly vaporized in a Thorazine-fueled zombie stomp. (As one patient later demanded of the band, "Why are we in here, but you're not?") The Ramones simply wore tight white T-shirts, black leather jackets, and jeans with the knees blown out—a nod to the fact that a punk may also have done time as a hustler. They woefully confessed in one song, "Fifty-third and Third, and I'm tryin' to turn a trick / Fifty-third and Third, you're the one they never pick." Looking back now on period photos from the mid-to-late 70s, the Ramones' uniform, as if they really were brothers, albeit from a Saturday-morning cartoon, was actually what most punks wore at the time: jeans, sneakers, a T-shirt, and a leather jacket. Nothing particularly outrageous in that. Even in this scattershot reminiscence, a bigger picture isn't difficult to form. Because whether specific or nondescript, all these various looks would intersect in something called punk, which we can clearly see as much more the embodiment of a pervasive attitude than a particular style. And so if there are multiple and contradictory versions of what punk was and what it meant, it's simply because just about everything that starts from the ground up, self-invented by those who are living through transformative periods themselves—in equal parts fact and fiction, and which is mostly comprehensible in retrospect—is sure to be endlessly contested. And it defies being neatly crammed into someone else's time capsule, or a museum, which often serves the same function. If the appropriation of punk—what Marc Bolan would call a "rip off"—turns out to be a cheap holiday in other people's history, no one should pretend to be surprised.

Out of the Blue and into the Black

The 1980 film Out of the Blue, directed by and starring Dennis Hopper, takes its title from the Neil Young song "My My, Hey Hey." The lyrics, referred to in Kurt Cobain's suicide note many years later, insist: "Rock and roll is here to stay / It's better to burn out / Than to fade away." And Young, the ultimate 60s hippie grappling with his relevance in the change of the times, sets punk and Elvis Presley in symbiotic opposition to one another: "The king is gone but he's not forgotten / This is the story of Johnny Rotten." Hopper's daughter in the film, portrayed by Linda Manz in possibly her greatest performance, is equally obsessed with Elvis and punk, as she struggles with a father in prison, teen confusion, and the reality of feeling stranded in the Canadian woods. In its opening scene she's cocooned in the overgrown cab of Hopper's rig at night, working the CB radio with lonely truckers out on the road.

![]()

Linda Manz in Out of the Blue.

“Hello, this is Gorgeous. Anybody out there read me?”

“10-4, I read ya.”

“My handle's Gorgeous. Pretty Vacant, eh? My dad's handle's Flash. Subvert normality. You know what that makes us together?”

“Yeah, fuckin' nuts.”

“Fuuuuck you. Together that makes us Flash Gorgeous.”

“Flash Gorgeous?”

“Punk is not sexual. It's just aggression. 10-4 old buddies. Deee-stroy. Kill all hippies. I'm not talkin' at you, I'm talkin' to you.”

“That's 10-4.”

“An-arky. Disco sucks. I don't wanna hear about you, I wanna hear from you. This is Gorgeous. Does anybody out there read me?”

“10-4 Gorgeous, we read ya. Let's go dancing. How 'bout disco? Over.”

“Disco sucks. Kill all hippies. Pretty Vacant, eh. Subvert normality.”

“Sub- what normalities, Gorgeous? You're just a crazy little kid. Tell me, what's this Pretty Vacant? Over.”

In the beginning of the film, the Manz character wears blue jeans and a denim jacket, the back of which has been customized with Elvis's name and a guitar. It's the kind of thing that no punk would be caught dead wearing. But what Hopper seems to be saying—Hopper, who came out of the same turbulent 60s as Neil Young, and was just as much of a hippie cowboy—is that rebellion passes from one generation to the next, just as each is compelled, symbolically at least, to lay waste to what came before. "Kill all hippies, disco sucks." For Hopper, and perhaps for Young as well, the words of Alexander McQueen may be brought to bear: "Demolish the rules but keep the tradition." By film's end, Manz's character has slicked back her hair and fully embraced the look and attitude of Elvis, who was as feared by adults in the mid-50s as his Rotten and Vicious spawn would be in 20 years' time. Out of the Blue (Suede Shoes) and Into the Black (Flag).

Trash & Vaudeville

In the Fall song, "Head Wrangler," Mark E. Smith asks, "Why did you take that corny stuff I loved so much / and make it hip?" Punk bands and their fans had their own particular ways of dressing up, none of which were at first sold to them, but were made by them, often with limited means, or simply plucked off the dollar rack at Good Will. Thrift stores in the States and jumble sales in the UK defined the economy of punk, its initial self-style. Fashion wouldn't advance without it, without the street and the vernacular looks that it might borrow or steal. There's no revelation in that. But it's important to remember that fashion wouldn't enrich itself if everyone gets it "for free." Admittedly simplified, the equation is brilliant: if you invent it, we can sell it back to you at X times the price. Further refined and elevated to haute couture, the sky, and not the gutter, is the limit. Is it any wonder that each room in the Met's Chaos To Couture feels less like a gallery in a museum and much more like a store? In the words of Malcolm McClaren, the former manager of the Sex Pistols, the ultimate goal was to produce "Cash from Chaos," a formulation that sadly represents the corporate alchemy of our time, and that of the military/industrial state.

![]()

Left: Anya Phillips. Right: Arto Lindsay, Ikue Mori and Tim Wright of DNA.

What you find thrifting, at least what you encountered once upon a time, can transport you back to bygone eras. In San Francisco in the mid-60s, for example, members of the Cockettes, the preglam theater/performance group, would head over to the Salvation Army and come away with all sorts of finery, with boas, beaded dresses and tuxedos from the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. (One former member recalled that you could fill a bag on "dollar day," but they would stroll out the door without so much as a passing glance at the register.) Against a gender-bent psychedelia, the Cockettes were able to camp out as refugees from the Jazz Age, dissolve the stereotypical image of "hippie" in a Victorian acid bath, and anticipate the time-travel glamfest that was Roxy—the Deco of decay. In New York in the 70s, thrifting meant that you could fill a closet with clothes that might last have been worn in a 60s Sam Fuller movie such as Underworld USA, the 50s TV series The Naked City, or Weegee's photos from the Bowery in the 40s, all of which zero in on the cool, noirish sources for the now-classic style associated with no wave. How the past becomes a skin for the present is an inverse form of molting, and suggests that those who inhabit these clothes were themselves castoff—from society but not from one another—and invented parts for themselves to play.

![]()

Paul Simon meets Television at CBGB, 1977. Photo by Lisa J. Kristal

Reinvention inevitably follows the rejection of a former life and its values, its shame and dreariness. Once painfully reborn, people dressing themselves are willing to "do the wrong thing," even remaining blissfully unconscious of the fact of any supposed transgression. "Doing the wrong thing" relates directly to the shambolic noise of punk, to its democracy, where it was simply not a requirement that anyone actually knew how to play an instrument. (And why, when someone really could, as with guitarists Tom Verlaine in Television and Robert Quine in the Void-Oids, you were thrillingly blown away.) In fashion, where everything is sold not once but twice, to the stores and to the public, intentionally throwing a wrench into the formula risks double jeopardy. And then of course there are the critics along the runway, who may be ready to pounce on any false move. People in the street who subvert the norms of fashion, even the most exhibitionistic who seek an audience, have no one to please but themselves. They are their own harshest critics. They perform for and compete with one another. This happens in fashion as well, though always under the sign of commerce and critical scrutiny. Free to do as they please, people in the street who make any sort of spectacle of themselves can be seen at the intersection of situationism and dandyism. One would think that a punk and a dandy are mutually exclusive antagonists, and yet situationism, essential to both, is the fulcrum by which they turn as they exert their power, whether seen or unseen, to subvert normality. The dandy, often passing in plain sight, possesses a greater mobility for covert operations—reconnaissance primarily—and is thus less frequently molested by law enforcement, though not perhaps by the passerby.

![]()

John Lydon mid-70s.

![]()

Left: Johnny Rotten as a Teddy Boy. Right: Rotten Johnny.

Playing against type was part and parcel of punk, yet in its lack of an overtly libidinal kick-it would have been unappealing to designers, specifically as it undermined the stereotypical image: ripped shirts pinned together, studded collar, spiky hair, ad nauseum. Imagine that the two poles of punk style in the mid-70s were: being more outrageous than your friends and, 180 degrees away, seeming to fit in, quietly unnoticed. This accounts in some measure for the opposing and overlapping looks from that time: tattered street urchin, well-scrubbed nerd, bored hustler, insurance adjuster, bug-eyed escapee from a psychiatric ward. Keep in mind that these descriptions tend to suggest a male persona. The continued strictures of male attire remind us that back in the punk era, among those who ventured beyond convention it was very often the men who stood out—and suffered the consequences. (Though let's not forget the cowardly attack on Ari Up, the dreadlocked singer from the Slits, who was jabbed in the back on a London street by a knife-wielding man who mockingly shouted, "Here's a slit for you!") A London punk who went to a rockabilly concert in '76 would likely take a beating. Thus the indelible image of Johnny Rotten smartly dressed as a Teddy Boy so that he might enter that world without abuse, and surely one of his greatest looks. But in Chaos To Couture, beyond the very first gallery and the archival footage that provides backdrop, there is very little on display that relates to the impact of how men dared to dress. This of course is a clear reflection of the industry's bottom line, which is women's wear, mapping the contours of the female body, particularly when brought to its highest elevation. Haute Chaos is a term that might have been applied to the Met's exhibition by Charles Frederick Worth, an Englishman who came to fame in Paris scarcely a half century after "the great terror," and is considered the father of haute couture. Worth famously dressed the Countess of Castiglione, who had been the mistress of Emperor Napoleon III (the last monarch of France), the Empress Eugénie, his wife, and the actress Sarah Bernhardt, as well as many notable women of their time who are all but forgotten in our own. Perhaps finer and more powdery, but dust just the same.

![]()

Left: The Countess of Castiglione. Right: Charles Frederick Worth.

Rectal Anarchy in the UK

At the risk of alienating American designers, and appearing to disregard punk's deep New York roots, the ascendance of what was an improvised style to full-fledged phenomenon occurred in London, where fads and scandal alleviate the boredom of tea and toast on yet another gray day, where anything even remotely enlivened is deemed "brilliant." The Met's show rightly accounts for the key positions and contributions of Malcolm McClaren and Vivienne Westood, with their succession of clothing shops that led to and helped articulate—and forever brand—the punk aesthetic: Let It Rock, Sex, Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die, and Seditionaries. As bestowed upon its final incarnation in the winter of 1976, their choice underscored the political climate in England at the time, with a chill that would linger and presage what lay ahead. In less than three years, Margaret Thatcher would become prime minister, the country's Iron Lady, or Reagan in drag. Although a grudge can be held and passed on from one century to the next, 1776 was ever so remote, and an all-too cozy moment would be shared by America and its former colonial masters. No wonder sedition, even as the name of a clothing shop, was in the air. Defined as conduct or language inciting rebellion against the authority of a state, sedition also stands for insurrection, and it would be reanimated once again. Jamie Reid, who designed or co-created many of the most infamous and lasting images associated with punk, had come out of Situationism. He had eagerly joined other pranksters on nighttime excursions to paste signs on store windows, declaring, "Shoplifters Welcome," and who placed stickers over ads, "Save Petrol—Burn Cars." Some of the record sleeves Reid created for the Sex Pistols, such as the Queen with a safety pin stuck through her nose, were banned. The cover for the album, Never Mind the Bollocks, landed them in court, where they were prosecuted with antiobscenity laws dating all the way back to the Napoleonic wars. 3 As they soon discovered, although the sedition laws in England have their source in an Act of Parliament from 1661, some of their provisions were still intact in the mid-1970s, and the Treason Act in the US Constitution, which derives in part from them, is very much with us today.

![]()

Vivienne Westwood.

This past May 6 on the red carpet leading to the Met's gala, Vivienne Westwood arrived, one of the only persons in attendance directly linked to the history of punk, a charter and still misfit member of the club. Rather than identify what dress she was wearing when prompted by Billy Norwich for Vogue.com's livestream, Westwood insisted on speaking about the badge that was prominently pinned to her chest.

“The most important thing is my jewelry, which is a picture of Bradley Manning. And I’m here to promote Bradley, and he needs public support for what’s going on with secret trials and trying to lock him away, and he’s the bravest of the brave and that’s what I really want to say more than anything. Because punk, when I did punk all those years ago, my motive was the same: justice and to try to have a better world. It really was about that. I’ve got different methods nowadays.”

Westwood's unexpected remarks in defense of the American Army private who was then being court-martialed for leaking the "Collateral Murder" video to WikiLeaks, along with hundreds of thousands of State Department cables—threatened to upend Wintour's well-scripted event. Within seconds, the camera abruptly swung from Westwood to Norwich's co-host, Hilary Rhoda, who segued to a video on the Met's curator, Andrew Bolton. It was Vogue's version of the bum's rush, an inelegant handling of an awkward moment. Now that the trial has concluded, Westwood can at least take solace in the fact that Manning was acquitted of the government's most serious charge, "aiding the enemy."

Westwood's prospects for appearing anytime soon in any of Vogue's publications seem slender at best, and she could probably care less. At 72 she is far more punk than people half her age, and half her mind. Just look at the silly, conservative frocks most of them wore that night. Only two of Westwood's dresses were to be seen on the red carpet, worn by actresses Christina Ricci and Lily Cole, who both looked fantastic. They were among the very few exceptions to an event that brought a wonderfully gruesome image to mind. For many of those in attendance at the Met's gala opening, had punk been the French revolution, their eyes would be staring up from a severed head in a wicker basket.

---

Notes.

1. In an email from Alan Belcher.

2. Email from Steve Lafreniere.

3. Interview with Jamie Reid, first published in Index, Jan./Feb. 1998, and reprinted in Bob Nickas, Theft Is Vision, JRP/Ringier, 2008.

Previously by Bob Nickas - Nic Refn and Ryan Gosling Driven... to Distraction